Our little project to hunt for organic molecules in prehistoric baby bottles, also known as feeding vessels, has entered its second phase. In a pilot study, Julie Dunne from the Organic Geochemistry Unit of the University of Bristol has tested small sherds of eight bottles, four of which returned positive results. One early Iron Age (c. 800-600 BC) feeding bottle found in a child’s grave indeed had milk residue of sheep, goat or cow in it; three others more likely contained a liquid or stew made from adipose animal fat, sourced from ruminants and pigs.

The prehistoric baby bottles are small and delicate, and some of the ones held in museum collections are complete. This presents a problem, as no responsible curator wants too many sampling holes in the artefacts. One way to circumvent the problem is to take a very small amount (< 1 g) of the ceramic matrix from the inside of the vessels with a drill after the surface has been cleaned; although this is still an invasive sampling method, it is much less visible from the outside than cutting through the whole vessel.

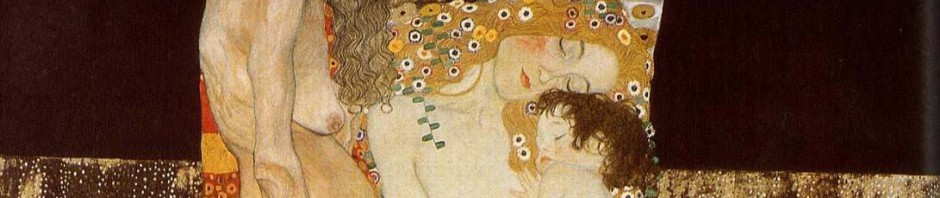

Two of the smallest feeding vessels after we sampled, from Straubing-Sand (Germany) and Stillfried (Austria). How small they are in comparison to my hand!

We were lucky to convince Julie Dunne to come to Vienna and show us how the sampling is done. She took samples of several vessels we could gather together in the vicinity of the Natural History Museum in Vienna. Both the Prehistoric and the Anthropology Department were very helpful and supported our endeavour. Julie also gave a talk entitled ‘Milk and molecules: how small molecules from ancient pottery tell us what people were eating in the past’ to give us more insights about her exciting day-to-day research.

Julie Dunne at work in the Natural History Museum in Vienna

All Julie needed to take with her to England was pottery powder wrapped carefully in aluminium foil (accompanied by letters of permission, just in case… the samples are crossing a border after all). We are looking forward to more exciting results.

References

Dunne, J. 2017. Organic Residue Analysis and Archaeology. Guidance for Good Practice. Bristol: Historic England.